THOK operational notes

I do a lot of detail-oriented "solving problems with code" and have always wanted to publish more of that (instead of leaving it buried in extensive but disorganized notes.) This particular blog is primarily about infrastructural development - running my homelab (to approximately professional standards), experimenting with blogging/publishing mechanisms, Debian packaging projects, and general messing about with python. It's a bit of a catch-all intended to keep infrastructure details out of my Massachusetts Ice Cream blog and Rule 3 among other things.

The biggest and last website to move over to new hardware was THOK.ORG itself. Bits of this website go back decades, to a slightly overclocked 486DX/25 on a DSL line - while static websites have some significant modern advantages, the classic roots are in "not actually having real hardware to run one". That said, it does have a lot of sentimental value, and a lot of personal memory - mainly personal project notes, for things like "palm pilot apps" or "what even is this new blogging thing" - so I do care about keeping it running, but at the same time am a little nervous about it.

(Spoiler warning: as of this posting, the conversion is complete and mostly uneventful, and I've made updates to the new site - this is just notes on some of the conversion process.)

Why is a static site complicated?

"static site" can mean a lot of things, but the basic one is that the web server itself only delivers files over http/https and doesn't do anything dynamic to actually deliver the content.1 This has security benefits (you don't have privilege boundaries if there are no privileges) and run-time complexity benefits (for one example, you're only using the most well-tested paths through the server code) but it also has testing and reliability benefits - if you haven't changed anything in the content, you can reasonably expect that the server isn't going to do anything different with it, so if it worked before, it works now.

This also means that you will likely have a "build" step where you

take the easiest-to-edit form and turn it into deliverable HTML.

Great for testing - you can render locally, browse locally, and then

push the result to the live site - but it does mean that you want some

kind of local tooling, even if it's just the equivalent of

find | xargs pandoc and a stylesheet.

For THOK.ORG, I cared very little about style and primarily wanted to

put up words (and code snippets) -

Markdown was the obvious

choice, but it hadn't been invented yet! I was already in the habit of

writing up project notes using a hotkey that dropped a username and

datestamp marker in a file, and then various "rich text" conventions

from 1990's email (nothing more than italic, bold, and code) - I

wasn't even thinking of them as markup, just as conventions that

people recognized in email without further rendering. So while the

earliest versions of the site were just HTML, later ones were a little

code to take "project log" files and expand them into blog-like

entries. All very local, README → README.html and that was it.

Eventually I wrote a converter that turned the project logs into

"proper" markdown - not a perfect one (while using a renderer helped

bring my conventions in line with what rendered ok, I never managed to

really formalize it and some stuff was just poorly rendered), just one

that was good enough that I could clean up the markdown by hand and go

all in on it. There was a "side trip" of using

Tumblr as a convenient mobile

blogging service - phone browsers were just good enough that I could

write articles in markdown on a phone with a folding bluetooth

keyboard at the pycon.ca conference

(2012) and get stuff online directly - I

didn't actually stick with this and eventually converted them back

to local markdown blogs (and then still didn't update them.)

Finally (2014 or so) I came up with a common unifying tool to drag

bits of content together and do all of the processing for the content

I'd produced over the years. thoksync included a dependency

declaration system that allowed parallelized processing, and various

performance hacks that have been overtaken by Moore's Law in the last

decade. The main thing is that it was fast enough to run in a git

post-update hook so when I pushed changes to markdown files, they'd

get directly turned into live site updates. Since I was focussed on

other things in the meantime (including a new startup in 2015) and the

code worked I hadn't really touched it in the last decade... so it

was still python 2 code.

Python 2 to Python 3 conversion

Having done a big chunk of work (including a lot of review, guidance, and debugging) on a python 3 conversion of a commercial code base, I was both familiar with the process and had not expected to ever need to touch it again - the product conversion itself was far later than was in any way reasonable, and most other companies would have been forced to convert sooner. It was a bit of a surprise to discover another 2000+ lines of python 2 code that was My Problem!

While there were only a few small CLI-tool tests in the code (which I was nonetheless glad to have) I did have the advantage of a "perfect" test suite - the entire thok.org site. All I had to do was make sure that the rendering from the python 3 code matched the output from the python 2 code - 80,000 lines of HTML that should be the same should be easy to review, right?

This theory worked out reasonably well at first - any time the partially converted code crashed, well, that was obviously something that needed fixing.

Here in 2025, with Python 3.14 released and the Python Documentary published, noone really cares about the conversion process as anything but a historical curiousity... but I had a bunch of notes about this particular project so I might as well collect them in one place..

- Trivia

#!update (I prefer/usr/bin/python3but there are solid arguments that/usr/bin/env python3is better; I just don't happen to usevenvorvirtualenv, so for my workflow they're equivalent.)print→print(),>>→file=- print itself was one of the original big obnoxious changes that broke Python 2 code instantly, it wasn't until relatively late thatfrom __future__ import print_functioncame along, which didn't help existing code but gave you a chance to upgrade partially and have shared code that was still importable from both versions. (Sure, library code shouldn't callprint- it still did, so it was still a source of friction. Personally I would have preferred a mechanism for paren-less function calls or definitions... but I wanted that when I first started using Python 2, and it was pretty clear that it wasn't going to happen. M-expressions didn't catch on either...Popen(text=True)was a fairly late way of saying "the python 2 behaviour was fine for most things, let's have that back instead of littering every read and write with conversion code." (universal_newlines=Truedid the same thing earlier, kind of accidentally.)file()→open()wasn't particularly important.long→int(only intumblr2thoksync, most of this code was string handling, not numeric) - this was just dropping an alias for consistency, they'd long been identical even in Python 2.import rfc822→import email.utils(parsedateandformatdatewere used in a few RSS-related places. Just (reasonable) reorganization, the functions were unchanged.SimpleHTTPServer,BaseHTTPServer→http.serverisinstance(basestring)→isinstance(str)string/byte/unicode handling was probably the largest single point where reasoning about large chunks of code from a 2-and-3 perspective was necessary; it's also somewhere that having type hints in python 2 would have been an enormous help, but the syntax didn't exist. Fortunately, for this project none of the subtleties applied - most of the checks were really that something was not anxml.etreefragment, it didn't matter at all what kind of string it was.

- Language improvements

except as- nicer to stuff an exception that you're intentionally poking at into a relevantly-named variable instead of rummaging around insys.exc_info. (raise fromis also great but nothing in this codebase needed it.)f=open()→with open() as fencourages paying attention to file handle lifetimes, reducing risk of handle leakage, and avoiding certain classes of bugs caused by files not flushing when you expect them to ("when the handle gets garbage collected" vs. the much more explicit and visible "when you leave the scope of thewithclause.)- argument "

tupleunpacking" is gone - this wasn't an improvement so much as "other function syntax made it harder to get this right and it wasn't used much, and there was a replacement syntax (explicit unpacking) so it was droppable." Not great but maybe it was excessively clever to begin with. - Python 2 allowed sorting functions by

id; Python 3 doesn't, so just extract the names inkey=(the actual order never mattered, just that the sort was consistent within a run.)

- Third-party library changes (after all, if your callers need massive

changes anyway, might as well clean up some of your own technical

debt, since you can get away with incompatible changes.)

- Markdown library

markdown.inlinepatterns.Pattern→InlineProcessor(the old API still exists, but some porting difficulties meant that the naïve port wasn't going to work anyway, so it made sense to debug the longer-lived new API.)etreeno longer leaked frommarkdown.util(trivial)- grouping no longer mangled, so

.group(1)is correct and what I'd wanted to use in the first place add→register(trivial)- different return interface

- string hack for

WikiLinkExtensionarguments no longer works; the class-based interface was well documented and had better language level sanity checking anyway.

- lost the

feedvalidatorpackage entirely sominivalidate.pydoesn't actually work yet (probably not worth fixing, external RSS validators are more well cared for and independent anyway. lxml.xml.tostring→encoding="unicode"in a few places to json-serialize sanely- in a few places, keep it

bytesbutopen("w" → "wb")instead

- in a few places, keep it

- Markdown library

Once the tooling got to the point where it ran on the entire input

without crashing, the next "the pre-existing code is by definition

correct" test was to just diff the built site (the output) with the

existing Python 2 version. The generated HTML code converged quickly,

but it did turn up some corrupted jpg files and other large

binaries; these were all repairable from other sources, but does

suggest that using more long-term content verification (or at very

least, "checking more things into git") should be an ongoing task.

(All of the damage was recoverable, it was just distressing that it

went undiscovered as long as it did.)

Attempting to get out of the blog tooling business

The tooling described here evolved around a particular kind of legacy

data and ideas, and isn't really shaped appropriately for anyone else

to use - it isn't even well-shaped for me to use on any other sites.

While the port did allow me to do some long-overdue content

maintenance of thok.org itself, it was getting in the way of a number

of other web-writing projects. Attempting to apply the Codes Well

With Others principle, I dug into

using staticsite, which was

simple, written in Python 3, based on markdown and Jinja2 and had

at least some recent development work. I ended up using it for

several sites including this one, though not thok.org itself (at this

time.)

I may end up going back and doing a replacement for staticsite, but

I expect to keep it shaped like staticsite so I can use it as a

drop-in replacement for the current handful of sites, and it's really

worked pretty well. (I will probably try to start with just a

replacement template - using plain HTML rather than upgrading to a

current version of React - since most of what I want is very simple.)

The other possibility is to move to pandoc as the engine, because it

tries hard in entirely different ways.

Things Left Behind

The old system had a notification mechanism called Nagaina that had a plugin mechanism for "probes" (AFS, Kerberos, NTP, disks, etc.) It had a crude "run all current probes, then diff against the previous run and notify (via Zephyr) if anything changed". The biggest flaw of this approach was that it relied on sending messages via MIT's Zephyr infrastructure; the second biggest was that it actually worked so I didn't feel that compelled to improve it (or move to something else.)

The new system has a bunch of systemd timer jobs that do things and

reports on them by email; OpenAFS notification is gone because the

cell is gone, and other things have simpler failure modes and just

need less monitoring. I have an extensive folder of possible

replacement notification mechanisms - some day I'll pick one and then

work backwards to tying anomaly detection and alerting into it.

-

This definition of static doesn't preclude things with client-side javascript - I've seen one form of static site where the server delivered markdown files directly to the client and the javascript rendered them there, which is almost clever but requires some visible mess in the files, so I've never been that tempted; it would also mean implementing my own markdown extensions in javascript instead of python, and... no. ↩

Historically, my online blog writing has always been distracted/dominated by the "plumbing" and other technical writing about blogging1, rather than writing itself2. Since I'm in the process of setting up new simplified infrastructure, I'm going to try that trick again3 but this time I already have a steady stream of things to write about because they keep leaking in to the Rule 3 project, and this pile of notes will keep them out of there - this is about Personal Infrastructure4 while that one is more Pontificating About Engineering and Infrastructure (for your next startup5.)

-

Otherwise known as "a homelab with delusions of grandeur", in the process of turning from an OpenAFS cell with a pair of 4x2T RAID-4 HP Proliant boxes into a single ASUSstor with 6x2T RAID-6 (7.3T) as a unix filesystem. (note: upgrade completed January 2025) ↩

-

Mekinok was a 2001 "instant infrastructure" startup; one of our lasting contributions was OpenAFS packaging in Debian to make setting up an AFS Cell (with Kerberos support) much less mysterious - which was useful to both TunePrint and MetaCarta over the next decade, and probably others. ↩

Background: the Topdon TC-004 Mini Thermal Infrared Camera

Matthias Wendel (youtube woodworker and author of

jhead) just posted a

video that showed off

the (sponsored/promoted) new Topdon TC-004 Mini1, a low-end

handheld (pistol-grip style) Thermal Infrared camera that was cheaper

than any of the attach-to-your-phone ones. The phone ones are clever

in a couple of ways:

- Very Small: I keep a first-gen Seek Thermal in my pocket with my keys, it's that small - great for diagnosing overheating equipment like robot grippers

- Cheap: the UI is entirely software, on the phone you already have; the phone supplies the battery and connectivity too

- Well Integrated:- even with a proprietary app to talk to the camera

(though the Seek Thermal device does show up under

video4linuxso it's not completely proprietary) you can just point Google Photos or Syncthing or Syncopoli at the folder and it's immediately part of your existing phone-photo workflow.

Handheld ones do have their own benefits, though:

- One-handed Use: Touch-screen triggers on phones are pretty clumsy and even when you "borrow" a volume button for the trigger, it's still usually not in a convenient place for holding and seeing the unobstructed screen.

- Much Easier to "Point and Shoot": the mechanics of a pistol grip are natural and comfortable, especially for being clear about what you're pointing at.

Even though the TC-004 Mini is pretty slow to power up, it's not complex, just hold the power button for "more seconds than you think you should" - five full seconds - compared to fidgeting with getting a device attached to your phone and getting an app running, it's dramatically more "ergonomic", and a lot easier to just hand to someone else to shoot with.

Great, you got a new toy, what's the infrastructure part of this?

The problem is that this is a new device and it doesn't really have any software support (apparently even on Windows, the existing Topdon app doesn't talk to it.) It does advertise itself as a PTP2 device:

Bus 003 Device 108: ID 3474:0020 Raysentek Co.,Ltd Raysentek MTP

bDeviceClass 6 Imaging

bDeviceSubClass 1 Still Image Capture

bDeviceProtocol 1 Picture Transfer Protocol (PIMA 15470)

and while gphoto2 does support PTP, it didn't recognize this device.

Turns out that while it's not generic, it's also not that complicated,

a little digging turned up a code contribution for

support from earlier

this year - with a prompt response about it getting added directly to

libgphoto2. Checking on github shows that there was a 2.5.32

release about a month

later

which is convenient for us - the immediately previous

release

was back in 2023 so this could have ended up a messier

build effort of less-tested development code.

Having a source release doesn't mean having an easy to install

package, though - usually you can take an existing package, apt-get

source and then patch the source up to the new upstream. Still, it's

worth poking around to see if any distributions have caught

up... turns out the Ubuntu packages are at 2.5.28 from 24.04 through

the literally-just-released-yesterday 25.10. Debian, on the other

hand, has a 2.5.32 package already in

Testing - it won't be in a

stable release for a while (the latest stable was only two months ago)

but that means testing itself hasn't had much time for churn or

instability.

Ok, you're running Ubuntu 24.04 though...

Now we're at the "real" reason for writing this up. gphoto2 doesn't

particularly need anything special from the kernel so this is a

great opportunity to use a container!

We don't even have to be too complicated with chasing down dependency packages, we can just build a Debian Testing container directly:

mmdebstrap --variant=apt --format=tar \

--components=main,universe \

testing - | podman import - debian-testing-debstrap

(Simplified for teaching purposes, see the end of the article for caching enhancements.)

podman image list should now show a

localhost/debian-testing-debstrap image (which is a useful starting

point for other "package from the future" projects.)

Create a simple Container file containing three lines:

FROM debian-testing-debstrap

RUN apt update && apt full-upgrade

RUN apt install -y gphoto2 usbutils udev

(gphoto2 because it's the whole point, usbutils just to get

lsusb for diagnostics, and udev entirely to get hwdb.bin so that

lsusb works correctly - it may help with the actual camera connect

too, not 100% sure of that though.) Then, build an image from that

Containerfile and

podman image build --file Containerfile --tag gphoto2pod:latest

Now podman image list will show a localhost/gphoto2pod. That's

all of the "construction" steps done - plug in a camera and see if

gphoto2 finds it:

podman run gphoto2pod gphoto2 --auto-detect

If it shows up, you should be able to

podman run --volume=/dev/bus/usb:/dev/bus/usb gphoto2pod \

gphoto2 --list-files

(The --volume is needed for operations that actually connect to the

camera, which --auto-detect doesn't need to do.)

Finally, you can actually fetch the files from the camera:

mkdir ./topdonpix

podman run --volume=./topdonpix:/topdonpix \

--volume=/dev/bus/usb:/dev/bus/usb gphoto2pod \

bash -c 'cd topdonpix && gphoto2 --get-all-files --skip-existing'

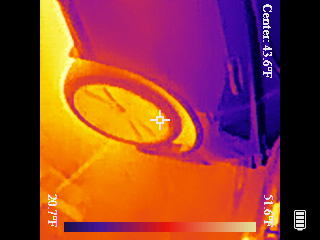

which should fill your local ./topdonpix directory with images like

this one:

Note that if you want to do software processing on these images - as

they come off the camera, they're actually sideways and have rotate

270 in the EXIF metadata - so your browser will do the right thing,

and a lot of other photo tools, but if you're feeding them to image

processing software, you may want to use jpegtran or exiftran to

do automatic lossless rotation on them (and crop off the black margins

and battery charge indicator - really, this camera is just

screenshotting itself when you ask it to store an image...)

Extras: caching

The mmdebstrap|podman import above is perfectly fine for a one-off

that works the first time. However, if you're iterating, you can save

yourself3 time and bandwidth by running apt-cacher-ng so that

you don't have to redownload the same pile of packages - 90 for the

base install, 91 for gphoto2 and dependencies. And sure, you'll just

reuse the debian-testing-debstrap image - but the configuration gets

set up by mmdebstrap in the first place, so you get those "for

free", even though the real benefit is in the other half of the

application packages.

First, actually install it:

$ sudo apt install apt-cacher-ng

The following NEW packages will be installed:

apt-cacher-ng

Configuring apt-cacher-ng

-------------------------

Apt-Cacher NG can be configured to allow users to create HTTP tunnels, which can be used to access remote

servers that might otherwise be blocked by (for instance) a firewall filtering HTTPS connections.

This feature is usually disabled for security reasons; enable it only for trusted LAN environments.

Allow HTTP tunnels through Apt-Cacher NG? [yes/no] no

Created symlink /etc/systemd/system/multi-user.target.wants/apt-cacher-ng.service → /usr/lib/systemd/system/apt-cacher-ng.service.

That's enough to get it running and automatically (via systemd)

start properly whenever you reboot.

Next, tell mmdebstrap to use a post-setup hook to tweak the "inside"

configuration to point to the "outside" cache (these are mostly

covered in the mmdebstrap man page, this is just the specific ones

you need for this feature):

--aptopt='Acquire::https::Proxy "DIRECT"'which says "any apt sources that usehttpsdon't try to cache them, just open them directly--aptopt='Acquire::http::Proxy "http://127.0.0.1:3142"'tells theaptcommands thatmmdebstrapruns to use theapt-cacher-ngproxy. This only works for the commands on the outside, run bymmdebstrapwhile building the container--customize-hook='sed -i "s/127.0.0.1/host.containers.internal/" $1/etc/apt/apt.conf.d/99mmdebstrap'After all of the container setup is done, and we're not running any more apt commands from the outside, usesedto change the Proxy config to point to what the container thinks is the host address,host.containers.internal4 so when the commands in theContainerfilerun, they successfully fetch through the host'sapt-cacher-ng. (99mmdebstrapis where the--aptoptstrings went.)

Final complete version of the command:

mmdebstrap \

--customize-hook='sed -i "s/127.0.0.1/host.containers.internal/" $1/etc/apt/apt.conf.d/99mmdebstrap' \

--aptopt='Acquire::http::Proxy "http://127.0.0.1:3142"' \

--aptopt='Acquire::https::Proxy "DIRECT"' \

--variant=apt --format=tar \

--components=main,universe testing - \

| podman import - debian-testing-debstrap

-

Not sure how much the promotion link matters to the price, it was around $150 at the time I ordered it; Matthias' affiliate link from the original promotion; if you don't want the tracking, here's a direct ASIN-only link (or you can just search for Topdon TC-004 Mini - try not to auto-correct to "topdown" instead :-) ↩

-

PTP is a predecessor to MTP for interfacing to USB cameras, but MTP is actually widespread (even on Linux there are half a dozen implementations of MTP, both as direct tools and filesystems.) ↩

-

While it does save wall-clock time, it also reduces the amount of load you put on the upstream servers - while they are free to you, they're funded by sponsors and as a member of the open source community, you should consider feeling just a little bit obliged to do your small, easy part towards decreasing Debian's avoidable expenses. (As a professional developer, you should be interested in efficiency and performance anyway, especially if you're automating any of this.) Of course, if you're just getting started and learning this stuff - welcome! And don't fret too much about it, a one-off here and there isn't going to make a difference, and you learning is valuable to the community too - just be aware that there's more that you can do when you're ready, or if you're doing this enough that getting into good habits matters. ↩

-

Docker has a similar

host.docker.internal;.internalis reserved at the internet-draft level as a domain that ICANN shouldn't sell, so this kind of thing won't collide with real domain names.) ↩

I have a typical "hacker homenet" - a few real external IP v4

addresses, and an internal 10/8 divided up into /24 chunks for

organization, not routing (for example, "webcams", "raspis",

"kindles", "laptops", "android stuff", etc) on the theory that I may

eventually want to lock them down differently or allocate specific

frequency bands for them, like making the webcams 2.4ghz only and

keeping laptops on non-colliding 5ghz.

While at home, the webcams are easily accessible to my phone and laptops via the magic of "being on the same wifi." What I wanted was a low-maintenance way to access them "on the road" from both my phone and my laptop. (Currently there's a high-maintenance path involving ssh tunnels that needs to be updated with every new camera - we're trading "do a little more configuration work up front and never touch the plumbing again" (wireguard) against various per-camera tweaks.)

What is wireguard, mechanically?

Wireguard is a widely deployed VPN mechanism built on some efficient cryptographic fundamentals - "but that's not really important right now". The details explain why it's good (and there are many articles starting with https://wireguard.com itself defending that), what we care about here is "what are the moving parts to set it up?"

Endpoint key pairs

As with ssh, you have a private key and a matching public key.

Mechanically, wg genkey generates the private key and wg pubkey

generates the public key from that. You keep the the private key

private - it appears in wg0.conf if you're using wg-quick (which,

for now, you are) and nowhere else. Arguably, don't even back it

up; if you're rebuilding the machine, it's simple to just generate new

keys and add the new pubkey on any peer systems. (If you have reason

to keep that connectivity working across a restore, then go ahead and

make sure you have Sufficiently Secure Backups for keying material,

just try and be explicit about what it's costing you.)

The wireguard tooling is a little odd in that it treats the (base64

encoded) public key as the name of the endpoint; primarily this

removes a layer of indirection and potential inconsistency, and it

makes some aspects of the configuration more tedious than it needs to

be - constants need names. (There may be hacks for this, but

wg-quick roundtrips the live state and will probably lose any

comments.) The idea seems to be that for small deployments it's not

that hard and for larger ones, you'll have more sophisticated

automation than just wg-quick.

The main point is that you'll have an obscure string of characters (the private key) that appears in exactly one place (on the machine that "owns" it) and a similar-looking string (the public key) that appears on every machine that directly connects to it. (We'll see later that there might end up not being very many machines, because ultimately this is a network system and other layers can provide plumbing without needing wireguard to explicitly do the work.)

Endpoint addresses

The "outside" of a wireguard connection is an IP address and port. These just need to be reachable (with UDP packets) from the machine you're configuring; if you're just going between machines on a campus or home net they don't even need to be public endpoints, but in the "outside world to homenet" configuration we're planning here, it's a lot easier if you have at least one public internet endpoint.

If all of the involved machines are public you can have them point to

each other and spontaneously connect as protected packets arrive; in

the modern dying age of IPv4, you're more likely to have one hub or

cloud machine that has a public address and most other systems talk to

it from behind NATs. In that case, the hub can't connect out to the

clients, but the clients can set a PersistentKeepalive which makes

sure that they keep pinging the hub and keeping the association alive

in the intervening routers - the tools on the hub will show an

endpoint, but that's not really the client endpoint, it's a transient

address on the NAT box that will still forward packets as-if-they-were

responses, through that existing association as long as it's kept

alive from the inside/client side.

(If you're using wg-quick on the hub, the main thing you'll want to

do is filter out the EndPoint entries after a save or down

operation, since they'll be useless. This is probably optional.)

AllowedIPs

The wg-quick config has an AllowedIPs value under [Peer] (as you

experiment, you can directly set this with wg set wg0 peer

... allowed-ips ....) This does two

things:

- it allows only packets from those source IP addresses through from the wireguard network interface when they come from that specific peer connection

- it does an

ip route addfor that same range of addresses on that wireguard network interface. (If you're not usingwg-quickyou need to do this yourself explicitly -wg-quick loadprints the literalip route addcommand it uses, but it should be pretty obvious.)

Basically it says "this subnet is on the far side of this wgN

network" - and that connections sent to those addresses should go via

wireguard, and connections from those addresses should get

responses via wireguard.

In the easy case, you've grabbed a bit of private-use network address

space (see RFC-1918) for your network and your "client" machines just

need to say "all of that is allowed from the hub"; the hub needs

individual (usually /32) ranges for each of the clients.

All of this explains why the AllowedIPs ranges on one machine can't

overlap: wireguard itself needs to be able to pick where a packet

goes.1

Hub and Spoke model

The details above are enough to generate a very minimal "network" - one "hub" machine with a public address, and one or more "spokes" that are anywhere that can reach that public address. (This does not include reaching each other via the hub, that's next.)

So, for every machine, apt install wireguard-tools so you have

wg-quick and a properly permissioned /etc/wireguard. Get a root

shell and cd there (it just shortens these steps if the working

directory is already "safe" and is already where things are going to

look.)

Generate the keys:

# cd /etc/wireguard

# wg genkey > privatekey

# wg pubkey < privatekey > publickey

Configuration here can go two ways:

- use

ipandwgcommands to get an active working system (an ephemeral one - rebooting will lose it all) thenwg-quick saveto stash the pieces - generate a

wg0.confwith the correct values, and thenwg-quick upto activate it (knowing that it'll activate the same way on reboot.)

The raw commands make things more incremental and help you understand

which pieces bring which functionality rather than making it a magic

whole; also if you're integrating it into your own script-generation

system (maybe directly managed systemd files) you want to know where

each bit goes. On the other hand, if you're just setting up half a

dozen machines by hand, hand-constructing some nearly identical

wg0.conf files is pretty quick too.2

Since there are advantages to both paths, I recommend doing what I did - do both! Set up one machine step by step, understand the resulting config, and just generate the config files for the other machines by hand, since the main difference will be the keys.

Hub and first spoke

Shortcuts we'll take here:

- While you can have multiple wireguard interfaces, we'll just use

wg0in all examples since we only need one for this basic setup. - We'll just pick

172.27/16for our RFC-1918 address space since- either you or your provider is already using some

192.168.*/24net and collisions are confusing 10/8isn't totally uncommon either, but it's also technically one single network- Docker is probably already using

172.17/16on your machine.

- either you or your provider is already using some

- We'll use literal

--priv-spoke-2--and--pub-hub-1--to substitute for the keys for those hosts; here we'll have multiplespoke-Nsystems and a singlehub-1. - We'll use

198.51.100.15as the public address ofhub-1(per RFC-5737 this is on TEST-NET-2, which is "provided for use in documentation".) - We'll just pick sequential wireguard-net addresses:

hub-1172.27.0.1spoke-1172.27.0.2spoke-2172.27.0.3

- Sample commands that start with

#(evoking a root shell prompt) run as root on any machine; commands that show ahost#prompt run as root on that particular named host. - Wireguard doesn't seem to have a standard port but some

documentation uses

51820so we'll do that too; feel free to change it to anything that doesn't collide with somethng else you're already running.

We've already generated privatekey and pubkey for spoke-1 and

hub-1 above (with raw wg genkey commands because wg-quick

doesn't give you any shortcuts for key generation anyway.) This

didn't configure anything, just generated a pair of text files on

each machine; we'll use the contents of those files below.

On both hub-1 and spoke-1, create the wg0 interface to hang this all

off of:

# ip link add dev wg0 type wireguard

Set the local addresses on each:

hub-1# ip address add dev wg0 172.27.0.1

spoke-1# ip address add dev wg0 172.27.0.2

Actually tell the kernel about the private key (by attaching it to the

wg0 interface):

# wg set wg0 private-key /etc/wireguard/privatekey

(Filenames are required by this particular interface to avoid exposing

the key via ps or history.)

Set up the first link from spoke-1 to hub-1:

hub-1# wg set wg0 listen-port 51820

spoke-1# wg set wg0 peer --pub-hub-1-- endpoint 198.51.100.15:51820 persistent-keepalive 25

The ports need to match, but it's not that important what they are.

Also you can use a DNS name here (ie. hub-1.example.com) if the

endpoint is actually in DNS.

Note that this link won't work yet - there's no route. You can

confirm this by running ping -c 3 172.27.0.1 and ip route get

172.27.0.1 on spoke-1; 100% packet loss, and the route shown will be

your normal default route (compare it to what you get from ip route

get 1.1.1.1) rather than via wireguard (which would show dev wg0.)

spoke-1# wg set wg0 peer --pub-hub-1-- allowed-ips 172.27.0.0/16

spoke-1# ip route wg0 172.27.0.0/16 add dev wg0

ping still won't work since this is only one direction, spoke to

hub3, but ip route get should show dev wg0 which is an

improvement. Set up the hub to spoke return path:

hub-1# wg set wg0 peer --pub-spoke-1-- allowed-ips 172.27.0.2/32

hub-1# ip route wg0 172.27.0.2/32 add dev wg0

Now you should have an encrypted channel between a pair of machines,

and you can access any TCP and UDP services on hub-1 from spoke-1

directly by IP address without any further configuration4. The

reverse is also true: you can ping 172.27.0.2 from hub-1 now, so

you might find this to be a useful way to demo a local service

securely - with a little more work, but without needing a permanent or

routable IP address for spoke-1 itself.

Once it works, if you're using wg-quick you can save the config:

hub-1# touch wg0.conf

hub-1# wg-quick save wg0

spoke-1# touch wg0.conf

spoke-1# wg-quick save wg0

(as of Ubuntu 24.04, save won't work unless the file already exists,

which might be a bug, or might be a way to defer setting correct

permissions?)

Second spoke

The hub and spoke can talk to each other just fine but that's probably

a lot less interesting than adding more spokes. Same key generation,

but let's create wg0.conf for spoke-2 directly:

[Interface]

Address = 172.27.0.3/16

PrivateKey = --priv-spoke-2--

[Peer]

PublicKey = --pub-hub-1--

AllowedIPs = 172.27.0.0/16

Endpoint = 198.51.100.15:51820

PersistentKeepalive = 25

On hub-1 you could do the wg and ip commands directly, but it's

simple to just add a new [Peer] stanza:

[Peer]

PublicKey = --pub-spoke-2--

AllowedIPs = 172.27.0.3/32

Note that the Hub side doesn't get an Endpoint, and thus can't use

PersistentKeepalive either. Also the AllowedIPs range is very

narrow, it says that this Peer link only carries traffic to and from

spoke-2's wireguard address. (For now - we will be adding more

later.)

Since nothing has run on spoke-2 yet, we can just bring it up

directly from the configuration:

spoke-2# wg-quick up wg0

On the hub, there's a little more work since wg-quick doesn't have

an incremental reload, so we bring it down and back up again:

hub-1# wg-quick down wg0

hub-1# sed -i -e '/^Endpoint =/d' wg0.conf

hub-1# wg-quick up wg0

It's probably safe to drop the Endpoint filtering here, since the "live" state will just be updated as soon as anything connects - but the hub would still generate noise for unreachable clients/spokes until then.

(The Ubuntu .service files pipe wg-quick strip to wg syncconf

which is a less disruptive path, since it leaves existing peer

sessions alone - I have not tested it at this time, but it's worth

looking at once you get things running.)

Now we can do the same ping and ip route get tests we did with

spoke-1 above and see that we can talk to hub-1 over wireguard.

We can also see that we can't talk to spoke-1 from spoke-2 -

the packets are getting to hub-1 but it isn't forwarding them.

Forwarding among spokes with iptables-nft

It's 2025 so we can assume you're using iptables-nft - the "new" (in

2014) kernel interface, but with a CLI layer that is still compatible

with 15 years of stackoverflow answers.5

There are three steps - spoke-1 and spoke-2 won't be able to

connect to each other until all three are done.

sysctl -w net.ipv4.ip_forward=1(depending on what else is going on with yourhub-1system this might already be set) lets your system forward packets at all. There's an ancient principle called "please don't melt down the Internet"6 that no system should ever forward packets "out of the box" without someone explicitly configuring it to do so - otherwise network admins would be spending vast amounts of time hunting down unexpected loops.iptables -A FORWARD -i wg0 -j ACCEPTwhich tells the kernelnftables/xtableslayer that incoming packets from wireguard (onwg0) should be fed to theFORWARD"chain" (for possible forwarding)iptables -A FORWARD -o wg0 -j ACCEPTwhich likewise configureswg0as an output interface for that chain.

I recommend trying the ping test after each step just to convince

yourself, but it's only after wg0 is configured as both an input and

an output interface that packets will flow through.

Again these commandline steps are "live", but not persistant - they'll

go away on reboot. Since they're specific to wireguard, if you're

using wg-quick it makes sense to add them to the [Interface]

stanza of wg0.conf:

PreUp = sysctl -w net.ipv4.ip_forward=1

PostUp = iptables -A FORWARD -i %i -j ACCEPT; iptables -A FORWARD -o %i -j ACCEPT

PostDown = iptables -D FORWARD -i %i -j ACCEPT; iptables -D FORWARD -o %i -j ACCEPT

You could use the exact commandline values here, but wg-quick

automatically substitutes the correct wg0 value when you use %i -

and all of the other tutorials and examples use %i - so you might as

well be consistent even if you're not going beyond this single-network

configuration.

Hub and Spoke and Hey Wasn't This About Webcams?

So far the spokes have been identical, but suppose spoke-2 is

really on our actual home internal network, with direct access to

a truly astonishing number of terribly cheap web cameras (attached

primarily to windows that face bird feeders - imagine each camera as a

cat staring out at the "kitty TV" provided by an outdoor bird

feeder... As A Service.)

Now that the rest of the wireguard connectivity is in place, we need to

- configure

spoke-1to know that the camera network is "over on wireguard somewhere" - configure

hub-1to know that the camera network is in the general direction ofspoke-2 - configure

spoke-2to masquerade (NAT) requests to the camera network out its local wifi connection and back.

Let's add to the shortcuts above:

- The web cameras are all on

10.11.12.*(This is not an actual/24, it's just a collection of addresses within10/8that share a common prefix.) - The local wifi interface on

spoke-2iswlp0s0f0and it turns out we don't care what address it has (in particular it does not need to be in the10.11.12.*range with the cameras.)

Step 1 is simple: just add , 10.11.12.0/24 to the AllowedIPs stanza

for the --pub-hub-1-- peer on spoke-1. (If you're doing this

manually, also do the explicit ip route add that wg-quick does for

you.) If you later give another spoke access to the cameras, this

is the only step you'll need to repeat. (Yes, I said this "wasn't a

/24" and it still isn't as far as the "real" network is concerned -

it's just a wireguard-specific fiction for a range of addresses.)

Step 2 is almost identical: on hub-1, add , 10.11.12.0/24 to

AllowedIPs, but this time specifically for the --pub-spoke-2--

peer. This is the primary "access control" - if the hub doesn't allow

this traffic in from wireguard, changing local configuration on any of

the receiving spokes (like spoke-1) won't do anything to get access

to it.

Step 3 on spoke-2 itself is almost unrelated to wireguard - it just

involves the same basic iptables-nft setup we did on hub-1 to

involve nftables at all, followed by a single command to NAT the

local interface:

PreUp = sysctl -w net.ipv4.ip_forward=1

PostUp = iptables -A FORWARD -i %i -j ACCEPT; iptables -A FORWARD -o %i -j ACCEPT; iptables -t nat -A POSTROUTING -o wlp0s0f0 -j MASQUERADE

PostDown = iptables -D FORWARD -i %i -j ACCEPT; iptables -D FORWARD -o %i -j ACCEPT; iptables -t nat -D POSTROUTING -o wlp0s0f0 -j MASQUERADE

The FORWARD chains arrange for xtables/nftables to care about

wireguard packets at all; the iptables -t nat -A POSTROUTING -o

wlp0s0f0 -j MASQUERADE lines feed packets that are heading out

wlp0s0f0 into the source address rewriting machinery (MASQUERADE)

so that the those devices think the connection is coming from

spoke-2's wifi address, so they know where to send the responses

(the responses also get rewritten so they actually reach spoke-1 over

wireguard.)

Note that we don't need to say anything about the addresses we're

rewriting for here - it's implicit in the use of wlp0s0f0, it'll be

any address associated with that interface, which in this case is

actually 10.0.0.0/8, though the AllowedIPs rule (specifically the

ip route part of it) on hub-1 will prevent this from having any

packets outside of the 10.11.12.* range. Exercise for the reader:

encode the narrower limit here as well, perhaps directly with nft

commands, or perhaps just with a wlp0s0f0:0 sub-interface with a

narrower netmask?

Other Details

Benefits of wg-quick

wg-quick is "just barely enough" configuration to get a minimal

wireguard network off the ground - which made it a convenient place

for operating system packaging tooling to add quality-of-life

improvements; Ubuntu, for example, includes systemd .service files

that take care of restarting your wireguard network on boot.7

MTU

wg-quick does ip link set mtu 1420 up dev wg0 while running over

links that are themselves mtu 1500; this prevents fragmentation from

adding the 80-byte (IP v6) wireguard header to an already-MTU-sized

packet (documented on wikipedia.) If you're only doing v4 over v4,

you can save 20 bytes and use an MTU of 1440 - but if you're in a

situation where you care that much you likely don't need me to tell

you that you are.

Future work

It should be possible to fully VPN a browser using a podman

container and a namespaced wireguard tunnel (possibly using wireguard

over wireguard?) While it has some limitations (wireguard doesn't

transport multicast so mDNS/avahi doesn't work) it should be suitable

for most "operate from the correct network" cases. Stay Tuned.

Conclusion

Wireguard really has very few moving parts, but you really do need

to get all of them right at once to do simple things with it.

Fortunately there are helper tools like wg-quick, and wireguard

itself is built at a level that works smoothly with the rest of the

networking tools in Linux.

-

This doesn't mean you can't have redundant connections to the same place - you just need to do the balancing yourself at another level? ↩

-

in the "pets vs cattle" debate, a handful of pets isn't wrong as long as you have an honest assessment of your trajectory and have time to rework things when the stampede arrives. After all, if Moore's Law lets you just have "one machine and a backup", maybe you don't need a whole Kubernetes cluster... ↩

-

You could demonstrate this with

tcpdump -i wg0onhub-1while running thepingonspoke-1. ↩ -

As long as they are listening on "any" interface - for example,

sshdor a typical web server, which show up as*:22or*:443inlsof -i tcpornetstatoutput. ↩ -

You can check this by running

iptables -Vand confirming the output contains(nf_tables). If you don't get that, you're usinglegacyiptables, and you may need to check if your kernel is new enough to even have wireguard. ↩ -

RFC-1812 section 2.2.8.1 is more concrete about the 1995-era "hidden pitfalls" of having "an operating system with embedded router code". ↩

-

See "Common tasks in WireGuard VPN" which explains using

systemctl enable wg-quick@wg0to turn on systemd support, and howsystemctl reloadlets you add or remove peers, but that[Interface]changes generally need a fullsystemctl restart(still more convenient than anythingwg-quicksupplies directly. ↩

One problem with having decent iptables compatibility layers for

nftables is that there's a dearth of documentation for the new

stuff; even 2024 stackoverflow questions (and answers) just use the

iptables commands underneath. So, when I first set up the "obvious"

nft commands to redirect :80 and :443 to internal non-privileged

ports (which then the "quadlet" PublishPort= directive would

re-namespace internally so that nginx would see them as 80 and

443 again) it worked, but only from off-box - connections (to the

dns name and thus the outside IP address) from on box didn't go

through that path. Not great, but most of my searching turned up

incorrect suggestions of turning on route_localnet so I just left

it that way.

Then a Christmas Day power outage led me to discover that there was a

race condition between the primary nftables service starting up and

populating the "generic" tables, and my service adding to those

tables, which caused the forwarding rules to fail to start.1

At least the command error showed up clearly in journalctl.

Application-specific tables

The one other service that I found using nftables is

sshguard2 - which doesn't depend on the service starting

at all. Instead, sshguard.service does nft add table in an

ExecStartPre and a corresponding nft delete table in

ExecStartPost - then the sshguard command itself just adds a

blacklist chain and updates an "attackers" set directly. This

doesn't need any user-space parts of nftables to be up, just the

kernel.

I updated my service file to do the same sort of thing, but all

expanded out inline - used ExecStartPre to add table (and add

chain), matching delete table in ExecStopPost, and the apply the

actual port redirects with ExecStart. The main rules were

unchanged - a prerouting tcp dport 443 redirect worked the way it

did before, only handling outside traffic; the new trick was to add a

oifname "lo" tcp dport 443 redirect to an output chain, since

locally-initiated traffic doesn't go through prerouting. (Likewise

for port 80 since I still have explicit 301 redirects that promote

http to https.)

The cherry on top was to add counter to all of the rules - so I

could see that each rule was firing for the appropriate kind of

traffic, just by running curl commands bracketed by

nft list table ... |grep counter and seeing the numbers go up.

Victory, mostly

The main reason for fixing localhost is that it let me run a bunch of "the websites are serving what I expect them to be" tests locally rather than on yet another machine. This is a bit of all-eggs-in-one-basket, but I'll probably just include a basic "is that machine even up" checking on a specifically-off-site linode, or maybe a friend's machine - really, if the web server machine is entirely off line I don't really need precise detail of each service anyway.

Slightly More Victory (2025-08-04 followup)

While setting up wireguard for access to some internal

webcams, I kept getting Empty reply from server errors from curl.

Switching to https just to see if I got different error messages

gave me a startling

* Server certificate:

* subject: CN=icecream.thok.org

which could only mean that I was talking to the webservers here... and

in fact, I was; tcp dport 443 is much too broad, and catches traffic

though this machine as well as to it. Adding an ip daddr for

the external IP address of the web server to the rule was enough to

correct the problem.

-

This is the "normal" systemd problem, where

After=means "after that other service successfully starts" which isn't good enough for trivial.servicefiles that don't explicitly cooperate. It might be possible to fix this by moving thenft -f /etc/nftables.conffromExecStart=toExecStartPre=(since it's aType=oneshotservice anyway) so that it exits before the job is considered "started" but thesshguard-inspired workaround is cleaner anyway. ↩ -

sshguard is a simple, configurable "watchdog" that detects things like repeated ssh authorization failures (by reading the logs in realtime) and responds with various levels of blackhole routes, using

nftablesto drop the packets. Professional grade, as long as you have an alternate way back in if it locks you out. ↩

There is a feature request from 2019 which is surprisingly1 still open but not really going anywhere. There are scattered efforts to build pieces of it, so for clarity let's write down what I actually want.

What even is "cron-like behaviour"

The basic idea is that the output of a job gets dropped in my mailbox. This isn't because mail is suitable for this, just that it's a well established workflow and I don't need to build any new filtering or routing, and it's showing up at the right "attention level" - not interrupting me unless I'm already paused to check mail, easily "deferred" as unread, can handle long content.

Most uses fall into one of two buckets.

- Long-timeline jobs (weekly backups, monthly letsencrypt runs) where I want to be reminded that they exist, so I want to see successful output (possibly with different subject lines.)

- Jobs that run often but I don't want the reminder, only the failure reports (because I have a higher level way of noticing that they're still behaving - a monthly summary, or just "things are still working".)

The primary tools for this are

- a working

mailCLI systemdtimer filessystemd"parameterized service" files that get triggered by the timer failing (or passing.)

The missing pieces are how to actually collect the output.

Journal scraping?

We could just trust the journal - we can use journalctl --unit or

--user-unit to pry out "the recent stuff" but if we can pass the PID

of the job around, we can use _SYSTEMD_UNIT=xx _PID=yyy to get the

relevant content.

(Hmm, we can get pass %n into the mailing service

(systemd.unit(5)), but not the pid?)

Separate capture?

Just run the program under script or chronic pointing the log to

%t or %T, and generate it with things we know, and then

OnFailure and OnSuccess can mail it and/or clean it up.

While it would be nice to do everything with systemd mechanisms, if

we have to we can have the wrapper do all of the work so we have

enough control.2

In the end

Once I started poking at the live system, I realized that I was

getting ahead of myself - I didn't have working mail delivery.3

Setting up postfix took enough time that I decided against anything more

clever for the services - so instead, I just went with a minimal

.service file that did

WorkingDirectory=...

Type=exec

ExecStart=bash -c '(time ...) 2>&1 | mail -s "Weekly ..." ...

and a matching .timer file with a variant on

[Timer]

OnCalendar=Monday *-*-* 10:00

The systemd.time(7) man page has a hugely detailed set of syntax

examples, and if that's not enough,

systemd-analyze calendar --iterations=3 ...

shows you the next few actual times (displayed localtime, UTC, and

as a human-readable relative time expression) so you can be confident

about when your jobs with really happen.

For the initial services like "run an apt upgrade in the nginx

container" I actually want to see all of the output, since Weekly

isn't that noisy; for other services I'll mix in chronic and ifne

so that it doesn't bother me as much, but for now, the confidence that

things actually ran is more pleasing than the repetition is

distracting.

I do want a cleaner-to-use tool at some point - not a more

sophisticated tool, just something like "cronrun ..." that

automatically does the capture and mail, maybe picks up the message

subject from the .service file directly - so these are more

readable. But for now, the swamp I'm supposed to be draining is

"decommissioning two machines running an AFS cell" so I'm closing the

timebox on this for now.

-

but not unreasonably: "converting log output to mails should be outside of systemd's focus." ↩

-

moreutilsgives uschronic,ifne, andlckdo, and possiblymispipeandtsif we're doing the capturing.cronutilsalso has a few bits. ↩ -

This was a surprise because this is the machine I'd been using as my primary mail client, specifically Gnus in

emacs. Turns out I'd configuredsmtpmail-send-itso that emacs would directly talk to port 587 on fastmail's customer servers with authenticated SMTP... but I'd never gotten around to actually configuring the machine itself. ↩

KPhotoAlbum has lots of built-in

features, but in practice the more convenient1 way to interface

with it from simple unix tools is to just operate on the index.xml

where all of the metadata is stored.2

kpa-grep

I started

kpa-grep back in

2011, around when I hit 90k pictures (I'm over 200k now.) The

originally documented use case was kpa-grep --since "last week"

--tags "office" which was probably for sorting work pictures out from

personal ones. (The fuzzy timedateparser use was there from day

one; since then, I'm not sure I've used anything other than "last

week" or "last month", especially since I never implemented date

ranges.) I've worked on it in bursts; usually there's feedback

between trying to do something with a sub-gallery, trying to script

it, and then enhancing kpa-grep to handle it. The most recent burst

added two features, primarily inspired by the

tooling around my Ice Cream

Blog -

- A

sqlite-based cache of the XML file. Back in the day it took 6-8 seconds to parse the file, on a modern laptop with SSD and All The RAM it's more like 2.5 seconds - the sqlite processing takes a little longer than that but subsequent queries are near-instant, which makes it sensible to loop overkpa-grepoutput and do morekpa-grepprocessing on it. A typical "pictures are ready, create a dummy review post for the last ice cream shop with all pictures and some metadata" operation was over a minute without the cache, and is now typically 5-10 seconds even with a stale cache. - Better tag support - mostly fleshing out unimplemented combinations

of options, but in particular allowing

--tagand--sinceto filter--dump-tags, which let me pick out the most recentLocationswhich are taggedice cream, filter out city names, and have a short list of ice cream shops to work with. (Coming soon: adding some explicit checks of them against which shops I've actually reviewed already.)

As far as I know I don't have any users, but nonetheless it is on

github, so I've put some effort into keeping it clean3; recently that's

also included coming up with a low-effort workflow for doing releases

and release artifacts. This is currently a shell script involving

debspawn build, dpkg-parsechangelog, and gh release upload which

feels like an acceptable amount of effort for a single program with a

man page.

pojkar

pojkar is a collection of

Flickr upload tools that work

off of KPhotoAlbum.4 The currently active tools are

sync-to-flickr and auto-cropr.

sync-to-flickr

sync-to-flickr is the engine behind a simple workflow: when I'm

reviewing photos in KPhotoAlbum, I choose particular images for

posting by adding the Keyword tag flickr to the image. Once I've

completed a set and quit out of KPhotoAlbum, I run sync-to-flickr

sync which looks for everything tagged flickr, uploads it to Flickr

with a title, description, and rotation (and possibly map coordinates,

except there are none of those in the current gallery.) There's also

a retry mechanism (both flickr's network and mine have improved in the

last decade so this rarely triggers.) Once a picture has been

uploaded, a flickd tag is added to it, so future runs know to skip

it.

After all of that, the app collects up the tags for the posted set of

pictures; since social media posting5 has length limits (and since

humans are reading the list) we favor longer names and names that

appear more often in the set; then we drop tags that are substrings

of other tags (dropping Concord in favor of Concord Conservation

Land since the latter implies the former well enough.) Finally we

truncate the list to fit in a post.

auto-cropr

Flickr has an obscure6 feature where you could select a rectangle on

a picture (in the web interface) and add a "note" to that region.

auto-cropr used the API to look for recent instances of that which

contained a magic string - then picked up the geometry of the

rectangle and cropped just that area, posting it as a new flickr

picture - and then cross linking them, replacing the original comment

with a link to the new image. Basically this let you draw the

viewer's attention to a particular area and then let them click to

zoom in on it and get more commentary as well as a "closeup".

Note that these "views" are only on Flickr, I don't download or back them up at all (I should fix that.)

fix-kpa-missing/kpa-insert

As part of the Nokia 6630 image fixing project

there ended up being a couple of different cleanups which I needed to

review carefully, so I wanted the tools to produce diffable changes, which

lxml doesn't really guarantee7. Currently, the XML written

out by KPhotoAlbum is pretty structured - in particular, any image

with no tags is a one-line <image ... /> and I was particularly

looking to make corrections to things that were fundamentally

untagged8/untaggable (for fix-kpa-missing) or insert lines

that were already one-line-per-picture, I just had to get them in the

right place.

When I started the image recovery, I ended up just adding a bunch of

images with their original datestamps (from 2005), but KPhotoAlbum

just added them to the end of the index (since they were "new" and I

don't use the sorting features.) So I had the correct lines for

each image (which checksums and dimensions), I could just chop them

out of the file. Then kpa-insert takes these lines, and walks

through the main index as well. For basically any line that doesn't

begin with <image it just copies it through unchanged to the new

index; when it finds an image line, it grabs the attributes

(startDate, md5sum, and pathname specifically) and then checks

them against the current head of the insertion list9.

Basically, if the head of the index was newer than the head of the

insertions, copy insertions over until that's no longer true. If they

match exactly - the original version just bailed so I could look at

them, then once I figured out that they really were duplicates, I

changed it to output rm commands for the redundant files (and only

kept the "more original" line from the original index.)

The output was a diffable replacement index that I could review, and

check that the "neighbor" <image> entries made sense, and that

nothing was getting added from elsewhere in the tree, and other basic

"eyeball" checks. Since I had to do this review anyway to make sure

I hadn't made any mistakes of intent, it made sense to write the

code in a "direct but brittle" style - anything weird, just bail with

a good traceback; I wouldn't even look at the diffs until the code

"didn't find anything weird." That also meant that I'd done the least

amount of work10 necessary to get the right result - basically a

degenerate case of Test Driven Development, where there's one input

(my existing index) and one test (does the new index look right.)

I also didn't have any of my usual user interface concerns - noone (not even me) was ever going to run this code after making this one change. I did keep things relatively clean with small helper functions because I expected to mine it for snippets for later problems in the same space - which I did, almost immediately.

For fix-kpa-missing, I'd noticed some "dead space" in the main

KPhotoAlbum thumbnail view, and figured that it was mostly the result

of an old trailcam8 project. I was nervous about "losing"

metadata that might point me at images I should instead be trying to

recover, but here was a subset that I knew really were (improperly but

correctly) discarded images - wouldn't it be nice to determine that

they were the only missing images and clean it up once and for all?

So, the same "only look at <image lines" code from kpa-insert,

extract the pathname from the attributes, and just check if the file

exists; I could look for substrings of the pathname to determine that

it was a trailcam pic and was "OK", plus I could continue with the

"direct but brittle" approach and check that each stanza I was

removing didn't have any tags/options - but just blow up if it found

them. Since it found none, I knew that

- I had definitely not (mis-)tagged any of the discarded pictures

- I didn't have to write the options-handling code at all. (I suspect I will eventually need this, but the tools that are likely to need it will have other architectural differences, so it makes sense to hold off for now.)

There were a couple of additional scripts cobbled up out of these bits:

fix-kpa-PAlbTNwhich looked for Photo Album ThumbNails from the Nokia project and make sure they didn't exist anywhere else in the tree since I was discarding the ones that I had real pictures for and wanted to be sure I'd really finished up all of the related work while I still had Psion 5 code in my head...find-mbmwhich usedmagic.from_fileto identify all of thePsion Series 5 multi-bitmap imagefiles (expensively, until the second or third pass when I realized that I had all the evidence I needed that they only existed in_PAlbTNsubdirectories, and could just edit the script to do a cheap path test first - effectively runningfileon a couple of hundred files instead of two hundred thousand.) This was just to generate filenames for the conversion script, it didn't do any of the work directly.

Conclusion

I now have three entirely different sets of tooling to handle

index.xml that take very different approaches:

kpa-grepuses SQL queries on asqlitecache of the entire index (read-only, and generates it by LXML-parsing the whole file if it's out of date)pojkardoes directly LXML parsing and rewriting (since it's used for uploads that used to be expensive, it does one parse up front and then operates on an internal tree, writing that out every time an upload succeeds for consistency/checkpointing)kpa-insert&c. treat theindex.xmlas a very structured text file - and operate efficiently but not very safely, relying on my reading the diffs to confirm that the ad-hoc tools worked correctly regardless of not being proper.

Fortunately I've done all of the data-cleaning I intend to do for

now, and the kpa-grep issue

list is short

and mostly releng, not features. I do eventually want a full suite of

"manipulate images and tags" CLI tools, and I want them to be faster

than 2.5s per operation11 - but I don't have a driving project

that needs them yet - my photoblogging tools are already Fast

Enough™.

-

"Ergonomic" might be a better word than convenient, but I have a hard time saying that about XML. ↩

-

This does require discipline about only using the tools when KPhotoAlbum itself isn't running, but that's not too big a deal for a personal database - and it's more about not doing updates in two places; it's "one program wins", not a file locking/corruption problem. ↩

-

Most of the cleanliness is personal style, but

lintianandpylintare part of that. This covers having a man page (usingronnto let me write them in Markdown) and tests (since it's a CLI tool that doesn't export a python API,cramlets me write a bunch of CLI/bashtests in Markdown/docteststyle. ↩ -

When I promoted it from "the stuff in my

python/exifdirectory to an Actual Project, it needed a name - Flickor is the Swedish word for "girls", and "boys" is Pojkar (pronounced poy-car.) ↩ -

Originally this was twitter support, then I added mastodon support, then twitter killed their registered-but-non-paying API use so I dropped the twitter support - which let me increase the post size significantly. This also simplified the code - I previously used bits of thok-ztwitgw but now I can just shell out to

toot. ↩ -

Notes actually went away, then came back, then got ACLed; they're also inconsistent: if you're in a search result or range of pictures (such as you get from clicking an image on someone's user page) the mouse only zooms and pans the image; if you edit the URL so it's just a single-image page, then you get rectangle-select back. I basically no longer use the feature and should probably do it directly client-side at some point, at which point the replacement tool should get described here. ↩

-

It may be possible to pick a consistent output style at rendering time, but that might not be consistent with future KPhotoAlbum versions, and I just wanted to stick with something that worked reliably with the current output without doing too much (potentially pointless) futureproofing. ↩

-

One subset was leftover trailcam pics from before I nailed down my trailcam workflow - most trailcam pics are discardable, false-positive triggers of the motion sensor due to wind - but initially I'd imported them into KPhotoAlbum first, and then deleted the discarded pictures - and this left dangling entries in

index.xmlthat had no pictures, and left blank spots in the UI so I couldn't tag them even if I wanted to. ↩↩ -

This is basically an easier version of the list-merge problem we used to ask as a MetaCarta interview question - because we actually did have a "combine multiple ranked search results" pass in our code that needed to be really efficient and it was a surprisingly relevant question - which is rare for "algorithm questions" in interviews. ↩

-

In fact, it would have made a lot of sense to do this as a set of emacs macros, except that I didn't want to tackle the date parsing in elisp (and

pymacsis years-dead.) ↩ -

perhaps instead of pouring all of the attributes and tags into

sqliteas a cache, I should instead be using it for an index that points back into the XML file, so I can do fast inserts as well as extracts? This will need a thorough test suite, and possibly an incremental backup system for the index to allow reconstruction to recover from design flaws. ↩

This was supposed to be a discussion of a handful of scripts that I wrote while searching for some particular long lost images... but the tale of quest/rathole itself "got away from me". The more mundane (and admittedly more interesting/relevant) part of the story will end up in a follow-on article.

Background

While poking at an SEO issue for my ice cream blog1 I noticed an oddity: a picture of a huge soft-serve cone on flickr that wasn't in my KPhotoAlbum archive. I've put a bunch of work into folding everything2 in to KPhotoAlbum, primarily because the XML format it uses is portable3 and straightforward4 to work with.

Since I wanted to use that picture in my KPhotoAlbum-centered ice cream blog5 I certainly could have just re-downloaded the picture, but one picture missing implied others (I eventually found 80 or so) and so I went down the rathole to solve this once and for all.

First Hints

The picture on flickr has some interesting details to work from:

- A posting date of 2005-07-31 (which led me to some contemporary photos that I did have in my archive)

- Tags for

nokia6630andlifeblog - A handwritten title (normally my uploads have a title that is just the on-camera filename, because they go via a laptop into KPhotoAlbum first, where I tag them for upload.)

As described in the Cindy's Drive-in story, this was enough to narrow it down to a post via the "Nokia Lifeblog Multimedia Diary" service, where I could take a picture from my Nokia 6630 phone, T9-type a short description, and have it get pushed directly to Flickr, with some automated tags and very primitive geolocation6. That was enough to convince me that there really was an entire category of missing pictures, but that it was confined to the Nokia 6630, and a relatively narrow window of time - one when I was driving around New England in my new Mini Cooper Convertible and taking lots of geolocated7 pictures.

Brute Force

I'd recently completed (mostly) a transition of my personal data hoard

from a collection of homelab OpenAFS servers (2 primary machines with

8 large spinning-rust disks) to a single AsusStor device with a half

dozen SSDs, which meant that this was a good chance to test out just

how much of a difference this particular technology step function

made - so I simply ran find -ls on the whole disk looking for any

file from that day8:

$ time find /archive/ -ls 2>/dev/null |grep 'Jul 30 2005'

The first time through took five minutes and produced a little over a

thousand files. Turns out this found things like a Safari cache from

that day, dpkg metadata from a particular machine, mailing list

archives from a few dozen lists that had posts on that exact

day... and, entirely coincidentally, the last two files were in a

nokia/sdb1/Images directory, and one of them was definitely the

picture I wanted. (We'll get to the other one shortly.)

Since that worked so well, I figured I'd double check and see if there were any other places I had a copy of that file - as part of an interview question9 over a decade ago, I'd looked at the stats of my photo gallery and realized that image sizes (for JPGs) have surprisingly few duplicates, so I did a quick pass on size:

time find /archive -size 482597c -ls

Because I was searching the same 12 million files10 on a machine with 16G of RAM and very little competing use, this follow-up search took less than two minutes - all of the file metadata was (presumably) still in cache. This also turned up two copies - the one from the first pass, and one from what seems to be a flickr backup done with a Mac tool called "Bulkr"11 some time in 2010 (which didn't preserve flickr upload times, so it hadn't turned up in the first scan.) Having multiple copies was comforting, but it didn't include any additional metadata, so I went with the version that was clearly directly backed up from the memory of the Nokia phone itself.

That other file (side quest)

So I found

482597 Jul 30 2005 /archive/.../nokia/sdb1/Images/20050730.jpg

and

3092 Jul 30 2005 /archive/.../nokia/sdb1/Images/_PAlbTN/20050730.jpg

in that first pass. The 480k version was "obviously" big enough, and

rendered fine; file reported the entirely sensible

JPEG image data,

Exif standard: [TIFF image data, little-endian, direntries=8,

manufacturer=Nokia, model=6630, orientation=upper-left,

xresolution=122, yresolution=130, resolutionunit=2], baseline,

precision 8, 1280x960, components 3 which again looks like a

normal-sized camera image. The 3k _PAlbTN/20050730.jpg version was

some sort of scrap, right?12

I don't know what they looked like back then, but today the

description said Psion Series 5 multi-bitmap image which suggested

it was some kind of image, and that triggered my "I need to preserve

this somehow" instinct13.

Wait, Psion? This is a Nokia... turns out that Psion created Symbian, pivoted to being "Symbian Ltd" and was a multi platform embedded OS (on a variety of phones and PDAs) until it got bought out by Nokia. So "Psion" is probably more historically accurate here.

The format is also called

EPOC_MBM in the

data preservation space, and looking at documentation from the author

of

psiconv

it turns out that it's a container format for a variety of different

formats - spreadsheets, notes, password stores - and for our purposes,

"Paint

Data". In

theory I could have picked up

psiconv itself, the

upstream Subversion sources haven't been touched since 2014 but do

contain Debian packaging, so it's probably a relatively small

"sub-rathole"14... but the files just aren't that big and the format

information is pretty clear, so I figured I'd go down the "convert

english to python" path instead. It helps that I only need to handle

small images, generated from a very narrow range of software releases

(Nokia phones did get software updates but not that many and it was

only a couple of years) so I could probably thread a fairly narrow

path through the spec - and it wouldn't be hard to keep track of the

small number of bytes involved at the hexdump level.

Vintage File Formats

The mechanically important part of the format is that the outer layers

of metadata are 32 bit little endian unsigned integers, which are

either identifiers, file offsets, or lengths. For identifiers, we

have the added complexity that the documentation lists them as hex

values directly, and to remove a manual reformatting step we want a

helper function that takes "37 00 00 10" and interprets it

correctly. So, we read the files with unpack("<L",

stream.read(4))[0], and interpret the hex strings with

int("".join(reversed(letters.split())), 16) which allows directly

checking and skipping identifiers with statements like assert

getL(...) == h2i("37 00 00 10")15. This is also a place

where the fact that we're only doing thumbnail images helps - we

have a consistent Header Section Layout tag, the same File

Kind and Application ID each time, and that meant a constant

Header Checksum - so we could confirm the checksum without ever

actually calculating it.

Once we get past the header, we have the address of the Section